Products You May Like

issues and explore the world through the lens of tax policy. Learn more about taxes with TaxEDU.

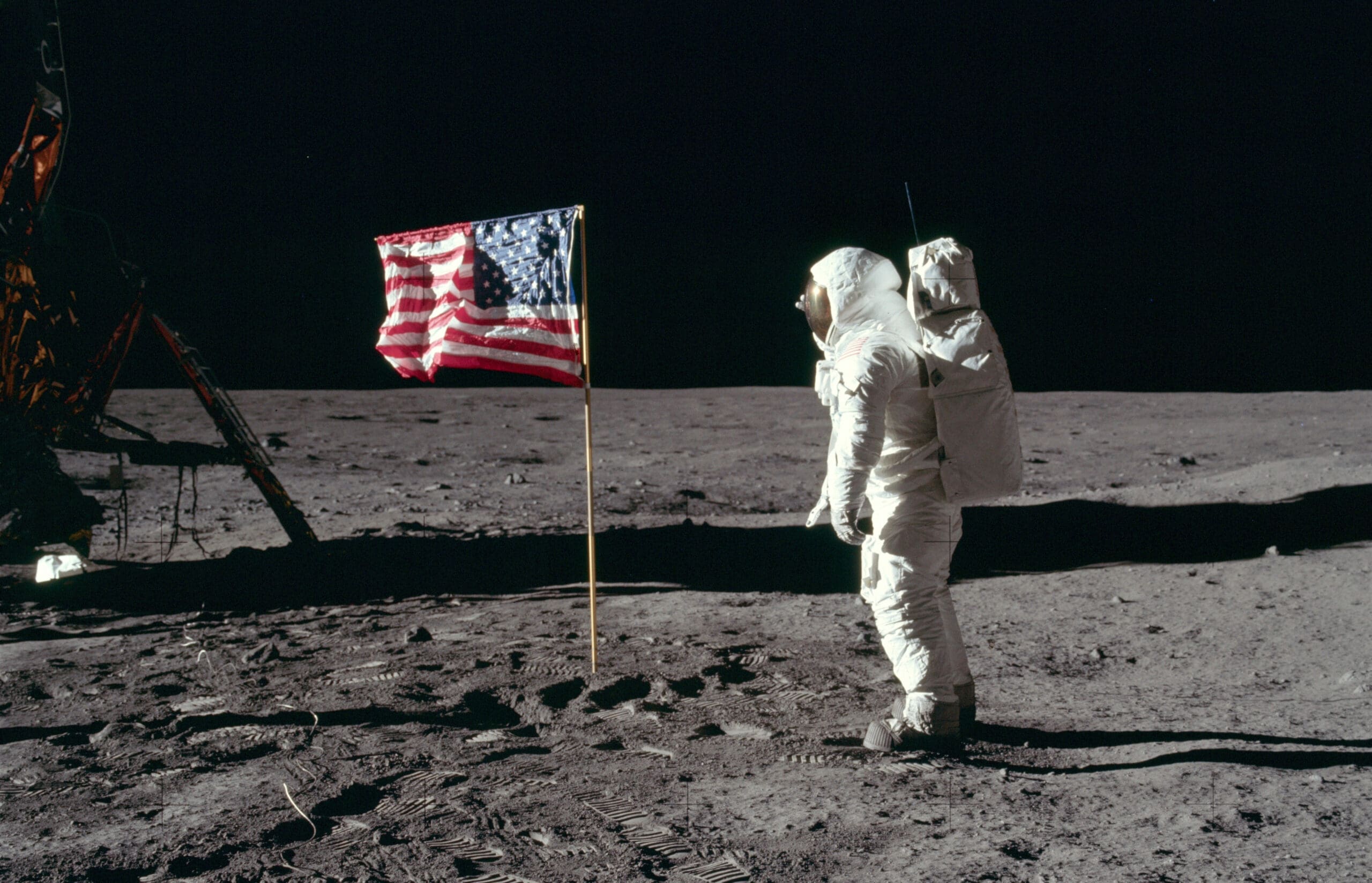

Fifty-five years ago, on July 24th, 1969, the Apollo 11 Lunar Module returned to Earth after becoming the first spacecraft to land humans on the moon. Though a historical accomplishment, the moon landing came at a cost.

From 1960 to 1973, the US federal government invested $25.8 billion into Project Apollo, which is about $318 billion in 2023 dollars. That comes out to $1,534 per person in the US at the time.

Project Apollo achieved its clear objective to put a man on the moon. But not all government spending projects are so simple (that is, if you consider flying a spaceship to the moon simple).

How Does Project Apollo Compare to Today’s Industrial Policy?

Project Apollo had specific, time-limited, non-economic goals: landing on the moon and outcompeting the Soviets in space.

Today, politicians across the political spectrum have shown a renewed interest in “industrial policy”— allocating government resources to specific industries to drive greater economic growth. But when industrial policies have both economic and non-economic goals, achieving simultaneous success in both areas can be challenging.

For example, two recent spending projects, the Creating Helpful Incentives to Produce Semiconductors (CHIPS) and Science Act and the InflationInflation is when the general price of goods and services increases across the economy, reducing the purchasing power of a currency and the value of certain assets. The same paycheck covers less goods, services, and bills. It is sometimes referred to as a “hidden tax,” as it leaves taxpayers less well-off due to higher costs and “bracket creep,” while increasing the government’s spending power.

Reduction Act (IRA), have tried to shift resources to semiconductors and green energy to accelerate economic growth. But they—and all industrial policy for that matter—risk investing money in the wrong places, leading to less economic growth. Sometimes, the market doesn’t fund something because of weak consumer demand or more efficient ways to allocate resources.

Historically, industrial policy has produced inconsistent results. One study analyzed 18 industrial policy projects over the last 50 years and found mixed results regarding industry competitiveness, job growth, and technological innovation. The economists conclude that “industrial policy can save or create jobs, but often at a high cost,” such as higher prices and taxes or job losses in downstream industries.

What’s Costlier, CHIPS or Moon Cheese?

The CHIPS and Science Act provided $79 billion in direct funding for the semiconductor industry and authorized Congress to spend another $200 billion on the industry in the future, meaning the total cost of the incentives will reach nearly $280 billion, an average cost of $822 per person in the US.

The IRA included a broad range of policies, but the Congressional Budget Office originally estimated its green energy tax credits would cost $271 billion. Since then, the costs have ballooned. Recent estimates of the total cost range from $780 billion to $1.2 trillion. Assuming an estimate of $990 billion (in the middle of this range), the IRA will cost an average of $2,926 per person in the US.

The Apollo program, therefore, was more expensive than CHIPS but significantly less expensive than the IRA.

What Are the Implications?

Project Apollo, with a specific, time-targeted goal, allows us to ask the following question: was winning the Space Race worth $1,500 per person in the US? For CHIPS and Science and the IRA, determining whether the costs are worth it isn’t possible yet because the jury is still out on how the projects will affect productivity and growth. But if experience tells us anything, they’ll likely redistribute resources from taxpayers to favored industries and companies without generating broad-based economic gains, and even potentially generating economic losses.

Stay updated on the latest educational resources.

Level-up your tax knowledge with free educational resources—primers, glossary terms, videos, and more—delivered monthly.

Share