Products You May Like

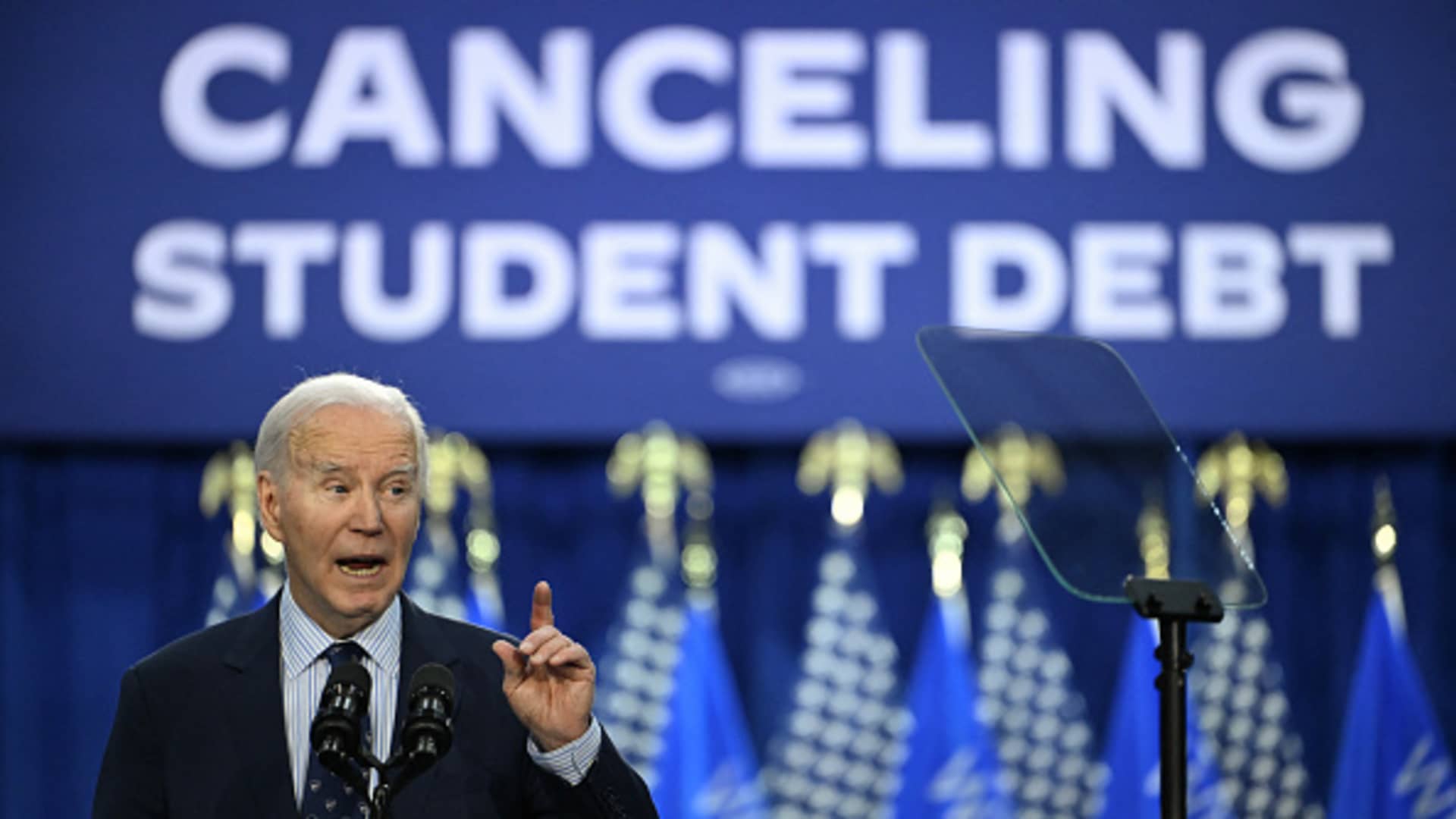

After the Supreme Court blocked President Joe Biden’s first plan to forgive student debt last summer, his administration set out to create a relief package that would survive legal attacks.

Here’s why the U.S. Department of Education thinks the new plan will endure.

The aid package is narrower

Biden‘s 2020 campaign promise to erase student debt was thwarted at the Supreme Court in June.

The majority-conservative court ruled that Biden didn’t have the authority to erase $400 billion in student debt without prior authorization from Congress. Biden had tried to forgive the debt of nearly all 40 million federal student loan borrowers, with many people getting up to $20,000 in cancellation.

This time, the Biden administration has narrowed its aid by targeting specific groups of borrowers, including those who’ve been in repayment for decades or attended schools of low-financial value. It hopes this will help the plan survive in front of a court that is skeptical of broad loan cancellation, experts say.

More than 25 million borrowers still stand to benefit from the program.

As a result, for critics of broad student loan forgiveness, Biden’s new plan looks a great deal like his first.

After the president touted his revised relief program on April 8, Missouri Attorney General Andrew Bailey, a Republican, wrote on X that Biden “is trying to unabashedly eclipse the Constitution.”

“See you in court,” Bailey wrote.

There’s a different legal justification

In addition to the fact that this effort is a more targeted aid program, the U.S. Department of Education is also using a different law — the Higher Education Act — as its legal justification. Biden’s first forgiveness plan was based on the Higher Education Relief Opportunities for Students Act, or HEROES Act, of 2003.

The HEROES Act was passed in the aftermath of the 9/11 terrorist attacks and grants the president broad power to revise student loan programs during national emergencies. The Biden administration initially tried to use this law because, at the time, the country was under national emergency status from the Covid-19 pandemic.

However, the conservative justices didn’t buy that argument.

Chief Justice John Roberts wrote in the majority opinion for Biden v. Nebraska: “But imagine instead asking the enacting Congress a more pertinent question: ‘Can the Secretary use his powers to abolish $430 billion in student loans, completely canceling loan balances for 20 million borrowers, as a pandemic winds down to its end?'”

“We can’t believe the answer would be yes.”

The HEA, which the Biden administration is now using, was signed into law by President Lyndon B. Johnson in 1965 and allows the Education secretary some authority to waive or release borrowers’ education debt.

When Sen. Elizabeth Warren, D-Mass., was running for president in 2020, she pointed to the HEA as a law that would allow her to deliver sweeping loan relief.

“This authority provides a safety valve for federal student loan programs, letting the Department of Education use its discretion to wipe away loans even when they do not meet the eligibility criteria for more specific cancellation programs,” Warren wrote in her student loan forgiveness proposal back then.

Biden administration is using rulemaking process

Biden initially attempted to forgive student debt through executive action, which the Supreme Court ruled was unconstitutional. The president has now turned to negotiated rulemaking.

More from Personal Finance:

How the affirmative action decision affects college applicants

Biden administration forgives $4.9 billion in student debt

College enrollment picks up, but student debt is a sticking point

The Biden administration hopes that by pursuing this lengthier and more involved regulatory process, it’ll be harder for the courts to strike down the relief.

Congress already authorized the U.S. Department of Education to issue regulations on specific aspects of the law, said higher education expert Mark Kantrowitz.

“Also, historically, the courts have given some deference to federal agencies with regard to regulatory authority,” Kantrowitz said. “That doesn’t mean the court won’t block new regulations, just that they are less likely to do so.”