Products You May Like

The taxation of large companies has been in the spotlight recently as governments around the world have sought to make significant changes to how corporate profits are taxed in a global economy. Last year more than 130 jurisdictions agreed to an outline of policies that would change where companies pay taxes and institute a global minimum tax of 15 percent.

The Biden administration has been supportive of these negotiations, but the changes should be reviewed in the context of recent policy changes in the U.S. and elsewhere, the general landscape of business taxation in the U.S., and potential challenges and risks arising from the global tax deal.

Here are four things to keep in mind amid the global tax debate:

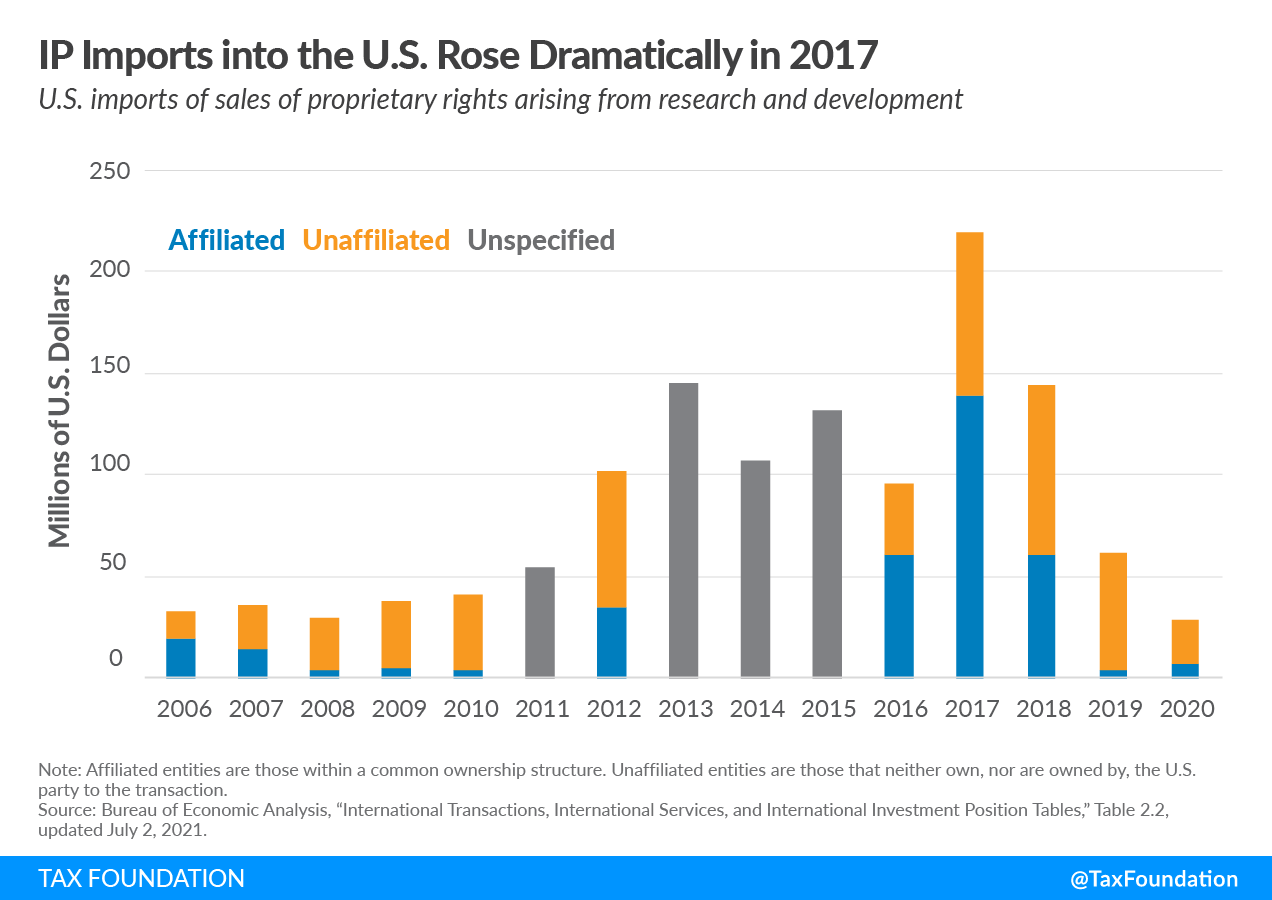

1. Profit-shifting incentives have decreased since 2017.

One goal of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) in 2017 was to reduce the incentives that companies previously had to hold significant profits offshore beyond the reach of the IRS. Recent data shows that those policy changes have been successful in redirecting previously offshored assets back to the U.S. and reducing artificial avoidance of the IRS by multinationals. Additionally, while the TCJA did reduce the tax burden on doing business inside the U.S., the overall tax burden on foreign income of U.S. companies was roughly unchanged.

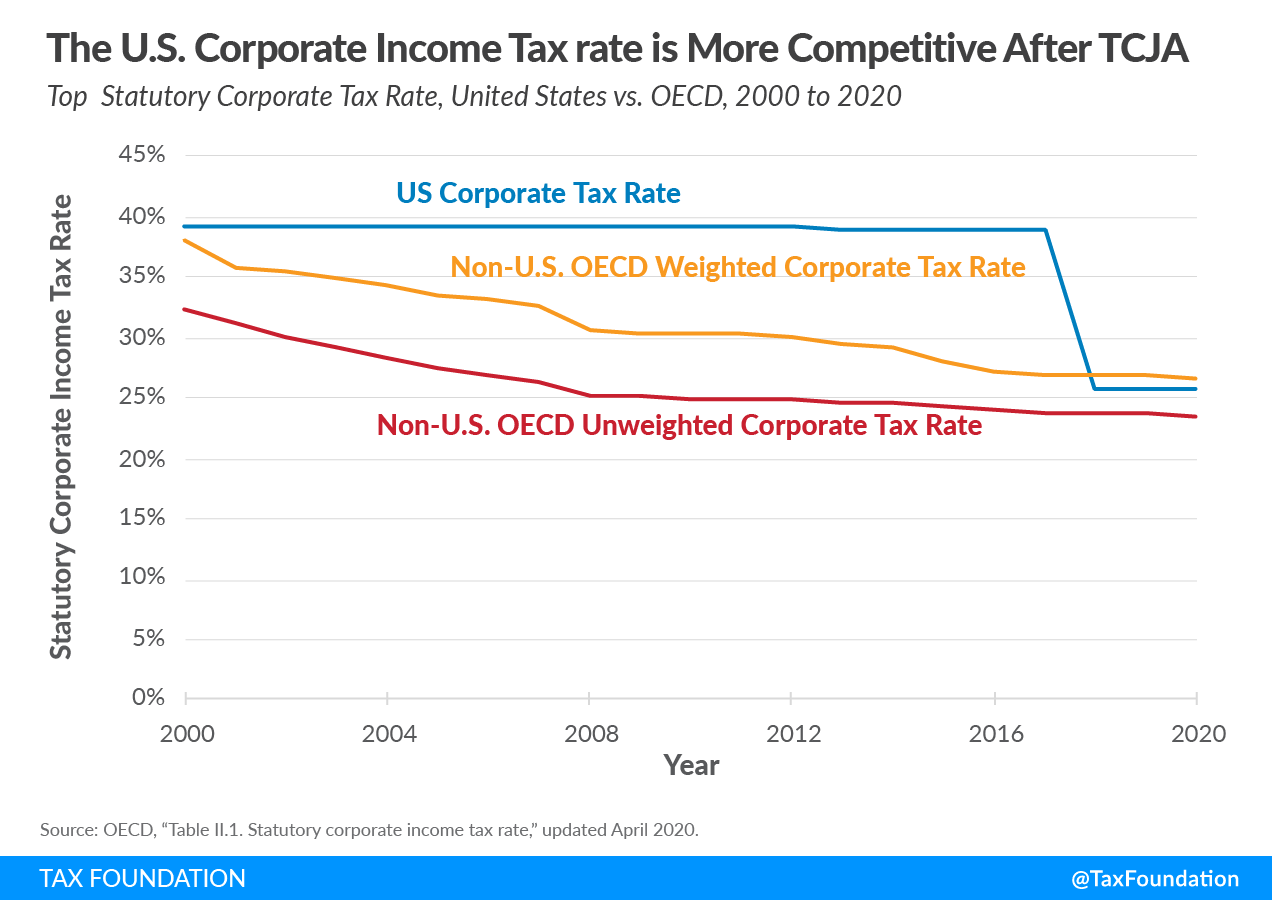

2. Corporate tax rates have settled in the low 20s.

The corporate rate cut from 35 percent to 21 percent reflects a broader trend of countries pursuing corporate tax rates of between 20 and 25 percent where the downward trend has leveled off in recent years. When including state-level corporate tax rates, the total U.S. tax rate on corporate income is 25.75 percent, above the worldwide average rate of 23.5 percent.

3. U.S. business tax revenue measures should reflect both corporate and pass-through business entities.

The U.S. tax system does not perfectly parallel the way other countries tax business income. The U.S. has a large pass-through business sector that is subject to the individual income tax. In fact, more than half of business income in the United States is reported on individual tax returns. This sector has grown relative to C corporations over the past 30 years, making comparisons over time and between countries more challenging. After adjusting for pass-through business tax collections, business tax revenue remains within its historical range at about 3 percent of GDP in 2021.

Similarly, U.S. corporate tax collections after adjusting for the size of the pass-through sector across countries matches the OECD average of 1.3 percent of GDP.

4. The U.S. corporate tax system remains incredibly complex.

The reforms brought in by the TCJA were not perfect. Many of the changes have made the tax system more complex for multinational companies. A 2020 assessment of the complexity of corporate tax codes of 69 countries placed the U.S. near the bottom of the rankings, at 50th place. Our neighbor Canada ranked 27th, and the United Kingdom took 28th place.

Unfortunately, the Build Back Better proposal which passed the House of Representatives last year would have made U.S. tax rules significantly more complex, especially for large multinationals. Not only would the proposals be more complex, but the approach would result in a higher tax burden for U.S. companies compared to what the outline of the global minimum tax has to offer. The U.S. approach to implementing the global minimum tax will matter a lot, and current proposals are aiming for a particularly burdensome approach.

As we wrote about in our options for tax reforms that promote growth and opportunity, one path forward for the U.S. system would dramatically simplify our international rules with a worldwide tax system and full credit for foreign taxes replacing GILTI while eliminating tax preferences that would not be recognized by the global minimum tax.

Policymakers need to be cautious and identify what actual problems need to be addressed before taking a difficult path to taxing multinationals. If the concern is over the U.S. tax base, then adopting policies that shrink the U.S. tax base seems counterproductive. The proposals could also strengthen (rather than reduce) the incentive for U.S. companies to avoid paying U.S. taxes.